Fostering Community through Conservation – Habitat Tuateawa

Follow the songs of Tui, Kākā and Korimako down the unpaved road from Coromandel Town to the endearing sanctuary that is Tuateawa. The warm embrace of native flora such as Harakeke, Nikau, and Rātā paint a moving picture of the wild and lively Aotearoa New Zealand that we yearn for.

Over the span of twenty years family, friends, and community members have proudly called the endemic locals back to their homeland - welcoming them with safety from introduced predators, and a glimpse back to the days when they were in charge.

Alan and Sue Saunders greet me at the driveway against a picturesque backdrop of the Hauraki Gulf - water glistening, waves crashing and kererū soaring. With open arms the people that breathe life into Habitat Tuateawa welcome me into their home, just as they have welcomed biodiversity through intergenerational conservation efforts. Here is their story.

Alan, Sue, and other dedicated members of the Habitat Tuateawa team sit down with me over a cup of tea and homemade baking, with countless stories of how their community has transformed their special place into a Biodiversity sanctuary to follow.

“His name is Bob” says Lorna. A Pīwakawaka that, without his tail, could pass for a feathered version of the golden snitch from Harry Potter. “He visits us every day”, perhaps seeking friendship but, more likely, eager for food. Is this what living in unison with our country’s endemic species looks like, I wonder.

Our conversation makes clear theirs isn’t an overnight success story, rather the result of countless volunteer hours, Bingo night fundraisers, trapline checks, and celebratory drinks.

“One of our organisation’s KPIs (Key Performance Indicators), was to have people complaining about the sound from too many birds”.

With a recent complaint of just the sorts it seems Habitat Tuateawa are well on their way to achieving their once-audacious goals.

It was a change in framing that invigorated the community to move beyond predator control and toward regeneration. We wanted “not just to kill, but to foster” Alan says with a metaphorical lightbulb enlightening the discussion once more.

During our conversation a conscious effort is required to not glance over every time a Tui or Kererū makes a fleeting visit to the local ‘singing post’. Alan contemplated cutting off the dead branch that partially obstructs their view of the Gulf, but decided against it when he realised it was the perfect spot for the birds to sing - after all maybe they wanted to enjoy the view too!

It’s not just the birds, impressive canopy, or views that are captivating here. The sense of community and connection that exists within the Habitat Tuateawa team has been foundational in allowing them to achieve their conservation goals.

Nicky has been on the journey since day one, and has helped their efforts evolve and take on a life of their own. She sits knitting woolen socks for the group’s members, an essential item when taking on the challenging terrain and unpredictable New Zealand weather.

“As more groups with conservation goals are established it is becoming clear that community-related goals may be as important to some people as ecological ones. It is a reminder that conservation is essentially a social endeavour.” Alan says.

With that in mind (and tea and homemade baking in our stomachs), we set off for a trapline just up the road to see the team’s work in action. Two of their most dedicated trappers, Libby McColl and Steve Garmey are our well-versed tour guides, and Alan Saunders is our personal encyclopedia.

On route to the trapline the team are eager to show us the community library appropriately located on the side of the road in an old buoy. Another example of conservation and community seamlessly interwoven.

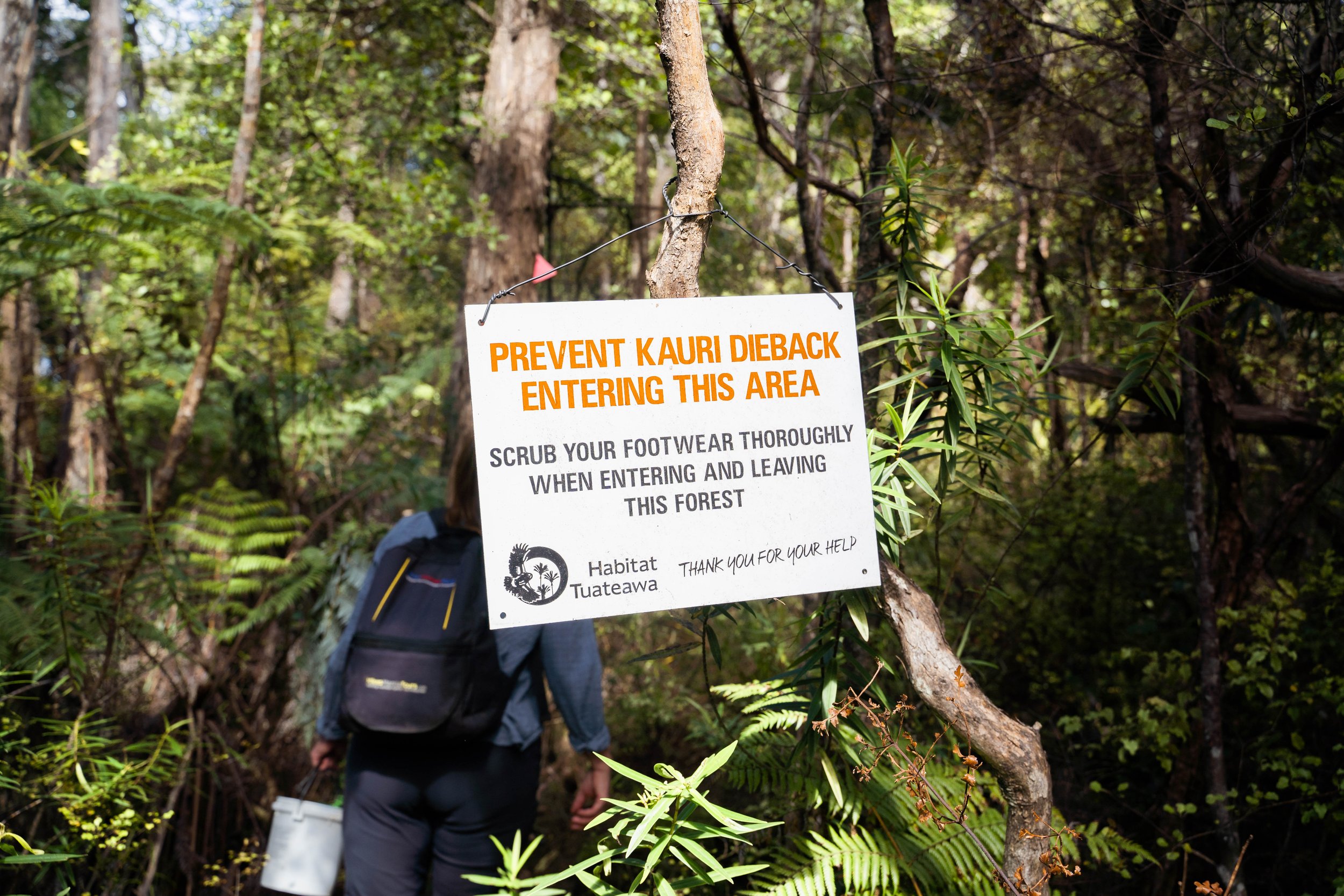

Before immersing ourselves in the native bush, we are reminded of another issue plaguing one of our iconic endemic species, Kauri dieback. We stop at the track’s cleaning station to remove all soil from our footwear and spray disinfectant to ensure we aren’t spreading the microscopic soil-borne pathogen to the kauri trees Habitat Tuateawa are working to protect. The team takes additional precautions having a designated pair of trapline shoes - an example of the holistic thought that goes into their efforts.

It doesn’t take long to spot traps, bait-stations, and educational signs beautifully designed by Libby who works as a sign-designer and artist when she’s not on the traplines. She holds a tub of double-tap (Diphacinone + cholecalciferol) to refill the bait stations as recommended by the Department of Conservation. It breaks down quickly and lowers the risk of secondary poisoning. I ask the team about their feelings toward using bait as a few locals have spoken out against its use.

“No one likes using poison, but it’s absolutely necessary”.

The goal of Predator Free 2050 is that killing introduced predators through trapping or bait will no longer be necessary. In the meantime they say it’s an important tool, having seen first-hand the impacts of baiting during a targeted time of the year in lowering possum and rat numbers, and ensuring native flora and fauna have time and safety to thrive.

We stop at a stoat trap and watch Libby unscrew its wooden bones to place an egg and pre-feed ‘blood’ lure to attract the species responsible for up to 60% of kiwi chick deaths across the country. In true small-town New Zealand style, the Department of Conservation provides the eggs to a local farm for conservation groups to pick up free of charge - a simple and effective aid to their trapping efforts. Requiring the equivalent of 12.5 fantail chicks everyday to survive, stoats wreak havoc on our endemic species. The team kills an average of 8-10 stoats a year, a seemingly small number with almost immeasurable benefits to their local flora and fauna.

So how do the team measure their impact, I wonder. This is an important aspect of predator management with many funders requiring impact metrics, and the team finds motivation in knowing how their efforts are making a tangible difference. Every 25 meters we see a monitoring tunnel where footprints of rats and stoats are recorded to give the team a record of population numbers. This is particularly useful around bird breeding seasons, and before and after their control operations.

Observations are also important as the team spend much of their time immersed in the places and alongside the species they are working to protect. Steve and Alan spot a plant they can’t identify - a rare phenomena that must be addressed. Snipping off a small branch, the team put it away for safekeeping until a trusty identification book off Alan’s shelf can come to their aid.

We started our walk in a young, regenerating forest that is beautiful but immature. Now we end in the encapsulating canopy of a mature, 1,000+ year old ecosystem. Our walk has been one into the past to inspire the future, a fitting metaphor for the journey this community conservation group has been on for the past twenty years. As the sunlight is absorbed by towering mataī, kohekohe, and columnar kauri, it feels like we have finally entered into the safety net of Tāne - God of the Forest.

So what’s next for the Habitat Tuateawa team? The sample species collected on our walk remains unidentified so no doubt Alan will continue searching for answers. Sue Saunders dreams of a night sky reserve to protect invertebrate friends too often forgotten, with Puriri moths making a regular appearance at their evening BBQ’s, and Ruru soon to follow. The traplines will continue to be maintained by dedicated volunteers such as Steve and Libby, and the Tuateawa community will be further strengthened by conservation efforts. The twenty year journey doesn’t end here, and neither does the plight for our endemic species.

Article by: Siobhan O’Connor

Photography by: Savannah Walker, Taken of You

If your community conservation group would like to share your story and be featured on our blog, please get in touch! If you are interested in volunteering in the Hauraki Coromandel head over to our Contribute page and read more.